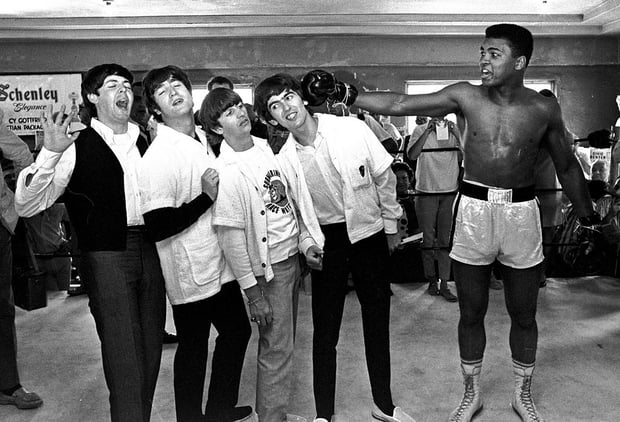

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Image via Wikimedia Commons

The Beatles got a lot right. After all, you don't become the most famous and beloved band in music history if you're constantly effing up right and left. But they were also pioneers, close pals, big personalities, prolific talents, and – perhaps most surprising of all – only human, which means they made some mistakes along the way. Luckily, you don't have to do the same with your band. Here are six lessons to learn from when John, Paul, George, and Ringo screwed up big time.

1. Keep your contracts

In 1960, the Beatles traveled from their native Liverpool, England, to Hamburg, Germany, for a string of engagements at seedy clubs in the city's infamous Reeperbahn district. Playing for pennies to drunken German audiences, providing the musical accompaniment to striptease shows, and sleeping in freezing quarters inside an adjacent movie theater wasn't exactly every musician's dream. So when the band received an offer to move on up to the more well-respected Top Ten Club for more money, they jumped at the chance, despite breaking their current performance contract.

Bad move. The manager of the venue who'd hired them then reported George Harrison for being underage in a club (he was 17), and the guitarist was deported. To add insult to injury, Paul McCartney and then-drummer Pete Best were deported a few hours later for attempted arson after they set a condom on fire for light (as you do) back at the theater, and John Lennon had his work permit revoked, also.

Moral of the story? If you've got an existing contract in place, don't break it. It's unprofessional and, in some cases, illegal. Better yet, before you ever sign a contract, be 100 percent sure of how you can get out of it if necessary, or change the language if that's something you anticipate. Also, don't perform in 21-and-over clubs if you're underage. Duh.

2. Know what's a good deal when it comes to merch

When Beatlemania swept through the US in 1964, the Beatles' manager, Brian Epstein, and his company NEMS were inundated with demands for merchandising rights. Epstein delegated the responsibility of merch licensing to a third party, who set up "Seltaeb" ("Beatles" spelled backward for the scholars among us), and cut a deal that gave Epstein's NEMS – and, in turn, the band – only 10 percent of the merch profits.

It's estimated that because of this catastrophic mistake, the Beatles lost around $100 million in merchandising. (Epstein did negotiate a 49 percent share in merch rights in '64, but that led to a lengthy and expensive court battle, and the opportunity to score the bulk of that sweet, sweet Beatlemania money was long gone.)

A brief aside: though many historians and Beatles fans alike are quick to blame Epstein for the mishandling of the merch rights, it's worth pointing out that no artist before the Beatles (not even Elvis) had faced the demand for novelty goods, clothing, likeness rights, etc. that the Fabs had.

There was no established precedent for licensing, so the Beatles really trailblazed the modern merchandising system (however uneven that road was paved). In fact, it might have been Epstein's mistake that ended up saving generations of artists since time, heartache, and tons of moolah.

The moral of the story? Manage your merch rights in a practical way. If you want to outsource, make sure you entrust someone with knowledge and experience to properly license your name and likeness. Most of all, make sure you negotiate a split that's fair for everyone involved (especially you).

3. Think before you speak

The Beatles gave lots of interviews – all the time. Maureen Cleave was a journalist the band considered a friend, so when she published an interview with John Lennon in early 1966, she thought nothing of including a quote that seemed to merely reflect Lennon's view on the Beatles' popularity in England:

"Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn't argue about that; I'm right and I'll be proved right. We're more popular than Jesus now; I don't know which will go first – rock 'n' roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It's them twisting it that ruins it for me."

When it hit newstands in Britain, it was met with crickets. But in the Bible-thumping, wholesome, American households of the South and Midwest, families were outraged. Radio stations instituted bans on the Beatles' music, and public record burnings were held. Even the Vatican denounced Lennon's words. It was a PR disaster set in motion just in time to complicate what would become the Beatles' final tour. Although Lennon issued a half-assed apology on several occasions through the years, at the time, it was a nightmare.

The moral of the story? Steer clear of hot-topic issues like religion and politics unless you're ready to face the repercussions, however nasty. In Lennon's case, he explained his words by essentially pointing out that the youth of the world would rather go to a Beatles concert than go to church, which is all well and good (and pretty accurate), but he should have said that the first time around. Don't make the same mistake. Live by the old adage: say what you mean, and mean what you say.

[The Indie Artist's Guide to Talking Politics on Social Media]

4. Make exceptions to your own rules sometimes

The Beatles' final tour in 1966 was rife with obstacles, but perhaps none was more contentious than their stop in the Phillippines. In Manila, the band received an invitation from then-First Lady Imelda Marcos to attend a luncheon at the Presidential Palace. Brian Epstein politely declined since the Beatles never accepted "official" invites from political powers on principle.

Marcos was incensed and offended that the Beatles didn't turn up for her event and, in retaliation, removed their security detail. As you can imagine, this put the band in life-threatening danger as fans freely swarmed them for the rest of their stay in Manila. It's said that John Lennon actually kissed the plane once they were winging their way out of the country.

The moral of the story? Make sure you're aware of where you're touring and have at least a pinkie on the pulse of what's going on there. If there's political unrest, maybe sit that country out this go 'round. And if you receive an invite from a dignitary (y'know, further down the line), you might consider going if it's not a move that would be detrimental to your career. In any case, make sure you evaluate opportunities on a case-by-case basis instead of making blanket judgments on what you as a band do and don't do.

5. Have a working knowledge of the music business

Brian Epstein tragically died of an overdose in 1967, just after the release of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Without him, the Beatles had no figurehead. They'd always trusted Epstein with all business matters while they concentrated on creating and experimenting in the studio. "I knew that we were in trouble [when Epstein died]," Lennon is quoted as saying in the Beatles' Anthology. "I didn't really have any misconceptions about our ability to do anything other than play music, and I was scared. I thought, 'We've had it now.'"

In his place, they turned to a motley crew of charlatans, lawyers, disreputable financial advisors, and others for guidance. It was the beginning of the end as the band began to disintegrate. The glue that held them together was gone, and now different influences were pulling them in different directions, making any negotiations complicated, if not impossible.

The moral of the story? Be prepared in case your manager disappears. No, it doesn't necessarily mean when he or she ascends to the big rock show in the sky. What would happen if your band's figurehead suddenly quit? Could you pick up the pieces yourself? Do you have a capable team of trusted advisors around you to help? It's not a bad idea to make a clause in your band agreement (you do have one of those, right?) about who does what if and when your manager takes off.

6. Communicate with your bandmates

The Beatles' breakup was anything but amicable. Reports state that during the recording of the band's last few albums, each member quit at least once. Finally, John Lennon formally told his bandmates he was quitting in mid-1969 but agreed to hold off on saying anything in public until after Abbey Road was released.

But before he did, Paul McCartney surprised everyone by publicly announcing his own departure from the Beatles the following April. The Daily Mirror published a simple headline, "Paul Quits the Beatles," which the general populous took to mean the band had broken up altogether. Later that year, McCartney infamously sued his other three bandmates to dissolve the Beatles' partnership, although the Fab Four wouldn't be completely free until 1975.

The moral of the story? Look, there are so many morals to the end of the Beatles' story. It reads like a sloppy reality show season finale full of backstabbing, rivalries, arguments, and on and on. One of the major issues lurking at the root of their discontentment was that each Beatle was exploring solo territory and anxious to strike out on his own. Add to that the terrible management situation (see above), outside influences, and perhaps a general sense of weariness and creative stifling, and it's not hard to see why the four lads would want to go their separate ways after 10 years together.

The problem is that communication was virtually non-existent; at times, the bandmates preferred to only speak to each other through their lawyers. If you're in a band, at minimum, the communication needs to be there. Otherwise, why are you even working with musicians you can't talk to at least professionally? Call it quits, and put the band out of its misery. And hey, if there's a silver lining to the Beatles' messy breakup, it's that you and your bandmates could go on to even greater success on your own. Or you could be Ringo. Whatever.

Allison Johnelle Boron is a music writer and editor living in Los Angeles. Her work has appeared in publications including Goldmine magazine, Paste, xoJane, and more. She is also the founder and editor-in-chief of REBEAT magazine, a digital publication focused on mid-century music, culture, and lifestyle. Follow her on Twitter.