Image via Shutterstock

Image via Shutterstock

This article originally appeared on Soundfly.

Songs are almost always built from sections that will feel very familiar, and yet they still have the power to bring us delightful surprises. How songs are put together has varied over the decades, based on taste, culture, and innovation, but there are some fairly standard musical segments in a song that contain their own specific functions. While the order will vary here and there, the scaffolding itself is easy identifiable.

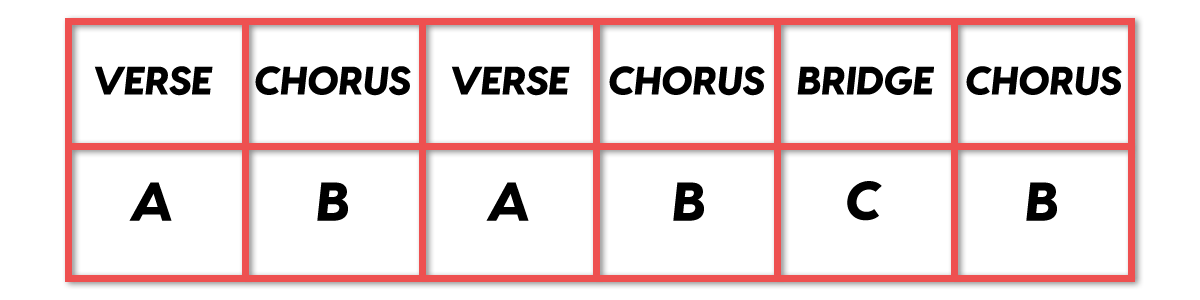

Here’s a very common and current song structure example:

You probably know this one inside out. It starts with a verse and moves to the chorus, which is repeated three times in this song. There are two verses, and they’ll probably have the same melody but different lyrics — those external details and plot progressions move forward through the verses, bubbling with rhyme.

Then there is an additional section, the bridge, which is optional, but it tends to feature a different chord progression, melody, and another lyrical perspective. It’s often only heard once over the course of the song. We get to know the chorus the best because of its repetition, and the title will most likely be in a really strong position within the chorus, if not the most repeated line in the song. Melodically, or lyrically, we can refer to the chorus as the hook as well.

Structure meets energy

Now, look what happens when we use the same structure, and map out the intensity and emotion of this same song.

Our original box framework seems a little modest now. The bridge has given us the highest level of intensity, while our final chorus has powerfully sustained that intensity in a climactic conclusion. But this doesn’t always have to be the case, of course. As songwriters, we’re free to manipulate and flex this grid to whatever structure and flow fits our message and intent!

For now, let’s get to some of the other pieces in this puzzle: our intro, our doubled third chorus, and our outro.

Think in 3D!

So while the building blocks of all songs have a lot of similarities, when they’re lined up in a linear narrative or story, they take on different roles and weight by virtue of their relative position in the song.

Verse two has to give us new information now that we’ve heard the higher energy chorus, in order to keep us hooked in. In turn, that will change the way we hear the chorus the next time around. Then, the bridge might serve to take us to an even higher level, where we’re met by the final choruses to pull out all the stops.

Wait a minute… aren’t we talking arrangement and production here?

Eventually, yes. In order to build the energy effectively, a bit of mixing and EQ will go a long way. But your song already needs that scaffolding in place, at a much earlier stage in the writing process. It’s the song’s energy flow path that really animates and elevates it, which is why you can build the same amount of emotional intensity with a song written for solo piano that you can with a fully decked-out EDM jam.

Think like an architect for a moment, in all three dimensions, and try to imagine that you have the ability to build up, down, left, right, inside, and outside.

Which brick first?

In keeping with the metaphor, we can say that pop songs are basically as modular as Legos. Like building blocks, you can reorient which block goes where, to very effective, creative ends. Some songs meet their listeners head first. Motown made it a habit to put the chorus at the song’s head — like Diana Ross and the Supremes’ “Stop! In the Name of Love,” where the chorus grabs the audience by the ear and never lets go.

Of course, many of Motown’s radio mixes were around 2.5 minutes long, so as to keep the energy level tight and extremely compressed. But what about the structure of a song like Bob Dylan’s “Jokerman” with all of its six verses?

In the hands of a less-gifted songwriter, the whole five-minute cut might have sagged under its own weight. But the introduction is minimal, and the chorus is simple and repetitive in contrast to the complex lyrics of the verses, with a vocal hook to provide contrast. And each verse has sections within it, providing welcome respite for the listener to absorb the outstanding imagery the writer provokes. A midway instrumental over the first chords of a verse section further balances the song. But the song is no less intense for its length or repeated structural elements.

Prosody: work with the weave!

Prosody means, essentially, how your words and music match. On a fundamental level, how they work together to convey emotional meaning — on a simple level, that might mean using minor chord progressions along with more somber lyrics, and major progressions or upward-moving chords (more on that below) to talk about triumph and positivity.

Prosody can have a profound effect on the intensity and energy of your songs that you can incorporate consciously in your writing. And there are even more subtle ways to utilize and develop intensity within the parts of your song.

The contour of your melody

You can match where your melody rises and falls with the repetition and flow of your lyrics, as well as the content of your lyrics. Just as lyrical phrases are made with groups of words, melodic phrases are constructed with small groups of notes known as motifs. Both melodic phrases and lyrical lines can be repeated — not necessarily at the same time or via the same pitch material. A small shift can make a big difference in the shape of your melody.

Current Billboard 100 songwriting practice tends to start verses off on a lower note than the pre-chorus, which will in turn be lower than the chorus. In other words, the melodic home base rises as the song grows in intensity. Reserve the highest notes for the most memorable song section. Why? So your listeners can scream it out in the shower, of course!

Rhythm of speech in song

The amount of time spent on the strongest syllables and where they land within each bar is part of prosody, too. Because lyrics are sung, they are filled with the rhythm of natural speech, and songwriters can really go to town here (evidenced most noticeably in rap and hip-hop). Where do your key words land? Are the longest andstrongest notes given to the most important syllables?

Perhaps the ultimate example is Dolly Parton’s “I Will Aways Love You”, brought to a zenith by Whitney Houston.

Intervals and rests

A word about something that exists in every single song, but we just don’t ever really notice it: space. Where will you put your nothing?

The vertical spaces between notes are called intervals, and they move your melody either up or down in pitch. The horizontal spaces between notes and beats are called rests, and they can be very short or several bars long. You can get a quick refresher on reading, writing, and utilizing sheet music in your practice from our free course, How to Read Music.

Never underestimate the value of space in songwriting, which can manifest in the form of waiting, anticipating, silence, and so many more emotionally engaging experiences.

Think about where you want to put nothing in your song. We need some of that, too! Hearing absolutely nothing at strategic times can heighten the intensity of a section, especially immediately before the occurrence of a particular line you want to emphasize.

But what about the groove?

Don’t faster songs have higher energy by definition? Not necessarily. Think about the verses of Village People’s disco classic, “YMCA,” and the repeated announcements on that first beat: “Young man!”

Then, at the end of the verse, the delightfully dotted line “there’s no need to be unhappy” throws us into an energy peaking pre-chorus of instrumental stabs on the beat, before launching back into the pick-up line for the chorus lyric: “it’s fun to stay at the Y.M.C.A.”

How’s the energy working in the song you’re writing now? Take a look at how its scaffolding is hanging together and consider, perhaps, reframing it to land a bigger punch.

Next up:

- 5 Exercises to Write More Creative Lyrics

- When, How, and Why to Break the Rules of Songwriting

- 7 Easy Things You Can Do Right Now to Get Out of a Songwriting Rut

- How to Write Songs That Get Stuck in People's Heads

- How to Find Co-Writers

Charlotte Yates is a New Zealand singer-songwriter and songwriting coach. She's just released her seventh album Then the Stars Start Singing and is tutoring at the Songwriters Retreat in June and October 2018.