Image via flypaper.soundfly.com

Image via flypaper.soundfly.com

This article originally appeared on Soundfly.

Cranky neighbors. A dearth of suitable space to stack amps. A shortage of cash. There are any number of obvious and legitimate reasons for learning to record your electric guitar tracks direct in. When you get this skill down pat, you’ll find the approach delivers a great deal of speed and flexibility without compromising too much on sonic quality.

Nice mics in front of tube amps in good rooms still have their place in the world of recording, but the reality is that great records have been made using the ampless approach – to the delight of thin-walled neighbors everywhere.

Many companies have developed pieces of all-in-one guitar hardware to fill this recording niche. Fractal, Kemper, and Line 6 all provide options that will cover every base. Just plug into the unit, then into your sound card, and play. However, these boxes can be seriously pricey. Instead, I’ll be taking you through a few approaches that are both cheaper and modular.

What's in the box?

Let’s assume that you’ve got some basic idea of home recording and a little studio setup that you can plug into. The only extra thing that you might not have is a direct box. Also known as a DI, these humble rectangles are one of the most misunderstood pieces of gear.

What all direct boxes exist to do is convert a hi-Z (or high-impedance) line-level signal to a lo-Z mic-level signal. They are also able to do other very useful tasks, like lift hum-generating AC ground loops, a typical gremlin of the small studio setup.

Image via flypaper.soundfly.com

Image via flypaper.soundfly.com

It’s useful to school up on DIs – a working knowledge of the basic mechanics and principles behind them will help you become a better audio engineer. But for this specific job, they exist to optimize the volume and enhance the clarity of the raw signal coming out of your guitar.

You’d likely be seeking an active direct box, since the majority of guitar pickups are passive and will benefit from the boost that comes from active electronics. If you’re a guitarist with active pickups, the converse applies: Get yourself a passive box. Radial and Whirlwind are reliable brands.

Don’t break the bank, but don’t cheap out on a DI either. Get something built to last, packing quality electronics ensuring great sound for years.

Okay, so now you’re all tooled up. Make sure your signal isn’t clipping, and then read on!

Method 1: software

Basically, in this method, the computer recreates every step of the signal chain as plugin effects in your DAW.

Amps and pedals are conjured up using digital approximations of analog circuitry – we’ll call these amp simulations. Capturing the sonic signature of certain speaker boxes is done using a process called convolution reverb. When a raw audio signal is “subtracted” from the same signal being recorded via a mic and cab, the leftover data preserves the EQ characteristic of the hardware and room.

Think of these speaker simulations as a specialist reverb that overlays the frequency characteristics of a mic, cab, and room over your signal. In practice, simulating a speaker requires two things. One is a reverb plugin that can load convolution reverb files (more on this later). The second is a collection of files called Impulse Responses or IRs. These get booted up in the reverb plugin and contain the imprint of a cab and mic combo. They’ll be named things like “Marshall 1960s cab with v30, SM57 mic on axis.”

Sound confusing? It kinda is. Maybe your DAW is one like Logic that already packs some of this software inside it. If not, AmpliTube is an old hand with this approach. One of the first on the market, it combined several classic amps, speakers, and effects under the hood of a nice GUI (graphic user interface). IK Multimedia released several versions of it, some free, some cheap, some souped up and pricey.

Image via flypaper.soundfly.com

Image via flypaper.soundfly.com

A newcomer on the scene is PositiveGrid’s BIAS FX (shown above). It’s a touch pricey for an entry-level user, but the software gets mad props from touring and recording musicians, who are attracted to the authenticity of the sound and the ability to create custom amps from scratch within the software itself.

But maybe you’d rather not spend any money at all. There are some free options out there.

LePou has modeled a bunch of valve heads, ranging from Marshall to ENGL to MESA/Boogie. The LeXtac, replicating a Bogner Ecstasy, is a mainstay of mine. It offers rich, clean tones on the yellow channel, throaty crunch on blue, and very usable saturation on the red. Nick Crow and Ignite Amps also have some cool stuff worth sifting through.

TSE Audio offer some incredibly useful free options, emulating a Maxon OD808 driver pedal and Tech 21’s ubiquitous Bass Driver DI. The former is perfect for driving an amp for that extra 15 percent of tonal goodness, the latter a one stop shop for DI bass, both at no-brainer prices.

Finally, here’s a zip file of some of my favorite free impulse responses to get you started on speaker simulations. Both LePou and Ignite Amps offer free impulse response loaders that you can run after your amp plugin.

Method 2: hardware

The software method offers great flexibility – you can record your part and modify the tone later at the mixing stage. But the hidden cost is recording latency. Modeling amps and cabs in the box will tax your system, especially as you begin to layer guitars.

Image via flypaper.soundfly.com

Image via flypaper.soundfly.com

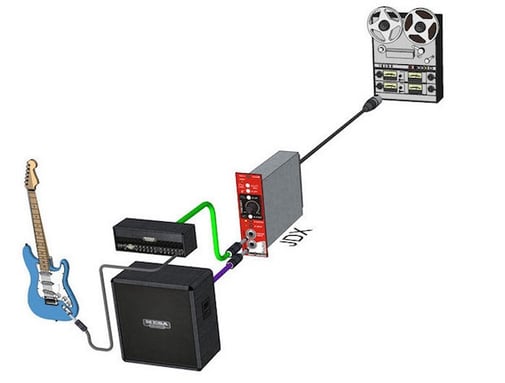

You already have an amp you like, and some pedals to boot. You just want to record quietly and quickly. It’s possible to buy a hardware speaker simulator that will allow for silent recording. Ranging from Two Notes’ large rack solution, Torpedo Live, to the compact Radial specialist JDX Reactor DI box, there are lots of options out there.

It’s important that the speaker simulator also functions as a “loadbox.” This means it replicates the impedance of an actual amp speaker. Preamps running without the right load can get damaged, so be careful and do your research here.

Many major amp brands offer guitar heads that are very suitable for a home rig, like Orange’s Tiny Terror. You could even do without a combo’s preamp or an amp head. Companies like Taurus are offering compact floor-based multi-channel amps, and Diago’s Little Smasher packs five watts (enough for recording) into a tiny package.

This approach will eliminate many latency issues. It’s also a somewhat cheap and cheerful alternative to getting one of the big-name rack systems outlined at the beginning of the article. However, since the sound of your amp source and hardware cab simulator are getting “printed” directly into the DAW, it lacks the flexibility of the software approach.

Think about what kind of guitarist you are and what your sonic goals are when considering these trade-offs. There is no overall perfect solution, but there is probably one that works much better for you.

That’s all for now. Happy tracking.

Next up:

- 3 of the Best Lightweight Guitar Amps You Can Get for $300 or Less

- Here's Why Your Arguments Against Amp Modeling Technology Are Totally Wrong

- Tube vs. Solid-State Amps: Which One Is Best for You?

Alex Wilson is a multi-instrumentalist, composer, and producer from Sydney, Australia. He founded the post-rock band sleepmakeswaves, with which he has toured Asia, America, Europe, and Australia. In his spare time he writes music for short films, produces bands, and subsists on altogether too much coffee. Alex is the instructor of the upcoming Soundfly course, Ableton Live Clicks and Backing Tracks.