All images via haulixdaily.com

All images via haulixdaily.com

This article originally appeared on Haulix Daily.

Before I dive too deep into this piece, I want to stress that I am a huge supporter of streaming services in general. The age of streaming has made it possible for artists at every level to continue making money on older releases long after consumer interest in purchasing those titles has been depleted.

We can argue all day about whether or not the royalty rate is acceptable (it’s not), but that is another conversation for another time. Streaming provides a steady stream of income for artists even when they have nothing new to promote, which in turn makes it possible for more artists to continue creating even when their latest release is less than well received by the general public.

Okay? Okay.

The more I think about the digital age and how it has impacted the entertainment industry as a whole, the more I realize that the film industry may have handled the war against piracy far better than those working in music. Unless a film is being released on VOD (video on demand), those interested in seeing a new title still have to buy a ticket and visit a theater in order to experience the film immediately following its release.

Those who are not willing to do that must wait for the film to hit VOD (usually three months after a theatrical debut) or wait for the title to be made available on streaming services like Netflix, Hulu, or Amazon Prime (which typically happens six to nine months after the theatrical debut). Some may choose to pirate the film before that happens, but if they do, their only viewing option is a significantly lower quality product, often captured by handycam or similar home video recording device.

This is not the case with music. Aside from a very select number of releases, every new album is made available on streaming services and in stores at the exact same time. More often than not, full streams of new releases hit the internet days before an album goes on sale, so even if you bought a copy through pre-order, you're able to access the music at the same time as everyone who didn’t bother to support the artist in question.

As long as you have access to YouTube, you can more than likely hear a new release in full two or three days before it’s available for sale, and if you have an account through Spotify, Tidal, or Apple Music, you can hear the vast majority of all music ever made available in the digital format for less than the cost of one album in stores.

This is a long way of saying new-release streaming on release day is a bad recipe for financial success. The ease of access doesn't raise the value of a product in the streaming age; it diminishes it. Why should consumers even consider paying $10 for an album they can essentially access for free? If I pay $10 a month for a streaming service and stream at least 1,000 songs each month, that means each song stream cost me one cent.

As we already know, artists do not receive even a penny per stream, so the actual value of each song played is less than a cent. Add offline streaming to the mix, which is the equivalent to downloading an MP3 onto your computer or mobile device, and you’ve basically got an endless supply of digital albums at your disposal whenever you need them.

[How Much Do the Most Popular Streaming Services Pay Per Stream?]

One could argue that the cost to produce a movie is far greater than the cost of producing an album, which justifies the need to push direct sales and rentals longer than music, but cost of production matters very little in this situation. No artist or record label releases music hoping to make just enough money to cover the cost of production. Artists and their labels want to make as much money as possible, and I believe they may be selling themselves short by rushing to streaming services on release day.

If you think about it, the promotional efforts for new movies and new albums are basically the same across the board. A trailer for a film is like a music video or single for an album. Filmmakers and actors do interviews to build awareness for their upcoming release just like musicians. Stills from the movie are like promo photos for an artist or group. Posters are album covers.

The difference is, when release day comes, you still have to go to a theater to see the film. It’s not available on your phone as soon as you wake up unless it’s purchased in advance on a VOD platform. Your excitement for a new film may been building for weeks or months, just like it would for new music, but on release day there is still a barrier to entry because studios understand that those who really want the product are still willing pay for it.

Those who are not as excited will wait for the cost to decrease or for the title to hit streaming platforms. Some will pirate the material, sure, but those people were never likely to buy a ticket or purchase the film in the first place.

If I had to pinpoint where music went wrong, I would wager it happened somewhere around the dawn of the new millennium. Napster targeted music long before film piracy was a hot topic, and no one really knew how to respond.

The music industry panicked, and soon the powers that be decided that the best way to fight piracy was to give everything away themselves in hopes of controlling the conversation. Their reasoning in this action was sound at the time: If labels and artists control how people access free content, they can directly interact with and market to fans that are eager to hear the material.

As time carried on, however, the ability to control the conversation by granting immediate/advance access began to shrink. Streams went from being hosted on an artist’s website to being available through third party platforms like SoundCloud and YouTube, which in turn made the material embeddable for anyone with a website.

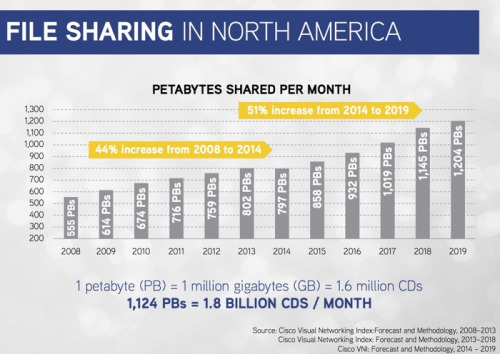

As you can guess, and as we now know thanks to numerous studies, this approach didn’t really solve anything except how easy it was for people to access music. According to a 2015 report from Cisco, music piracy is currently 48 percent worse than it was in 2008, and it’s expected to double by 2020.

A great example of immediate streaming hindering the sales potential of a record can be found by examining the rollout of Kanye West’s latest release, The Life of Pablo. The album, which allegedly received 250 million streams during in its first week of availability in February 2016, was released exclusively through Tidal without an option for fans to buy the record. This lead to a surge in Tidal signups, which in turn garnered a good deal of press for the platform, but it also led to a surge in music piracy.

According to a report from TorrentFreak, a rip of The Life of Pablo was pirated through torrent sites more than half a million times in that same first week. This does not take into account direct downloads of the pirated album – aka downloads from services like ZippyShare or MediaFire – which would likely place the number of stolen copies closer to, if not above, one million in a single week.

The Life of Pablo was eventually made available for download on April 1 for $20. The album moved the equivalent to 90,000 units and hit number one on Billboard, with more than half of its "sales" being generated by streaming equivalent albums. That means Kanye actually sold, at most, around 40,000 downloads. Compared to the 327,000 first-week album sales (pure album sales, no streaming) of his previous release, Yeezus, this is a dramatic 87 percent slide in first-week sales.

Furthermore, The Life of Pablo has not sold more than 1,000 downloads in a single week since its second week of availability, which puts Kanye’s total pure sales for this release to date (May 31, 2016) around 55,000 or less.

Kanye is not the only one covering low actual sales with big streaming numbers. The rate of streams is impressive, but the payout most likely is far lower than the total that could have been made from actual album sales. With this in mind, I posit that streaming’s impact on overall sales would be much lower if new releases didn’t hit streaming platforms for a month (or longer) after their initial release.

We cannot undo the last decade of content being made available instantaneously, largely for free, overnight, but we can adjust our release efforts moving forward in hopes of creating greater demand for downloads and physical product.

[With Streaming Ruling, Are Things Ever Going to Get Better in the Music Industry?]

Some believe people aren't willing to buy albums anymore because they don't want to risk purchasing something they might not like, but again, that is exactly what happens in the world of film. Trailers for new movies can be very misleading, and we’ve all been fooled by a good trailer for a bad movie. Still, consumers spend billions of dollars every year to see new titles of all sizes in theaters or on demand.

One could also argue the risk is even greater with film, as most ticket prices, especially for 3D films, are far higher than the cost of a record, and they only allow for a single viewing/entertainment experience. Downloads and physical sales allow consumers to spend time with the material, and more often than not, repeated plays of a record have a tendency to change people’s views of the material.

Fans who are unwilling or unable to purchase an album outright can and will wait for the record to be available on a subscription platform. What artists and labels alike need to do is create demand up front, push sales hard for a short period, then, only after the core buying market has been depleted, make the content available everywhere. Once your product is a click away, especially at little to no cost to the consumer, you’re forever fighting an uphill battle for sales where consumers win far more often than content creators.

Where do you stand on this issue? Do you think artists should make their albums available to stream on release day? Let us know in the comments!

James Shotwell is the digital marketing manager for Haulix. He is also a professional entertainment critic, covering both film and music, as well as the co-founder of Antique Records. Feel free to tell him you love or hate the article above by connecting with him on Twitter. Bonus points if you introduce yourself by sharing your favorite Simpsons character.